Surviving Prison in China with Poetry

I

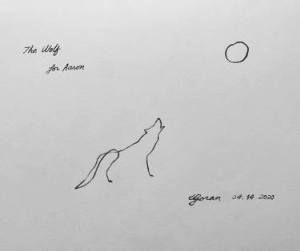

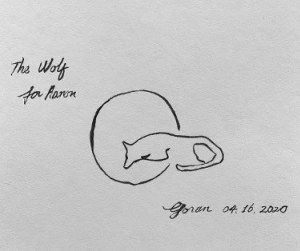

If I’m the wolf and you’re the moon

I’d tilt my head and sing to you

If I’m the wolf and you’re the moon

I’d make my bed in sight of you

Lonely, isn’t it? This is the first verse of “The Wolf,” a song written and sung by my 23-year-old son, Aaron. Each time I listen, it evokes memories of the 15 months I spent in solitary confinement as a political prisoner in Beijing, when Aaron was only five years old. Very high up on my cell’s wall there was a small window through which I would look every night in search of moonlight—really, any light—to reassure myself that it wasn’t all darkness.

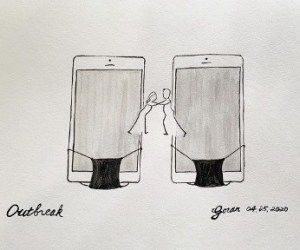

Sheltering at home during the COVID-19 crisis has brought back memories of that time. But when friends and journalists contacted me to ask for tips on dealing with confinement, my reflexive response has been to tell them it’s hard to compare the two. Quarantine physically isolates you, but thanks to technology we can maintain connections with people—even if they are on the other side of the globe. Social distancing isn’t really the right term; it’s physical distancing that we’re experiencing. While it’s difficult, it’s not like being in solitary confinement without a computer to facilitate connection to the internet, books to read, or even pen or paper to write with. When I was imprisoned, the only people I talked to were the ones I wanted to see least—interrogators who inflicted frequent physical and psychological torture.

There’s no comparison, I have told people.

But as our collective quarantine wears on, I have begun to understand why people would seek tips from someone like me. Both quarantine and solitary confinement are sudden dislocations that plunge you into a more isolated, less free, and far more frightening place. In both cases, it is the open-endedness of the experience that most fuels loneliness and exacerbates fear.

After returning to China in 2002 for the first time since surviving the 1989 Tiananmen Square massacre, I was imprisoned. I had spent the intervening years in Berkeley and Boston, earning doctorates in mathematics and political economy as I continued my activism. Despite being blacklisted by the Chinese government—which denied me the opportunity to renew my passport—I managed to enter the country on a friend’s passport. For two weeks before I was discovered, I worked with a growing labor movement on strategies for nonviolent resistance.

I was arrested, blindfolded, and put in the back of a car. During the four-hour ride that followed, I was gripped by intense and uncontrollable fear. I thought I was being taken to the place where they would shoot and kill me. I began to pray.

“Lord,” I said, “there must be a purpose. I may not understand. But whatever the outcome, I will happily accept it, if I am assured this is all your will. I ask you now to be with me, to help me overcome my fear. Wherever they take me, I know you will be with me. I know you will open the road for me.”

I kept praying like this, over and over, whispering these words to myself, and the fear gradually loosened its grip.

I was not killed but remained jailed until 2007. Nearly a quarter of my time—15 months—was in solitary confinement, where I sometimes felt that the isolation had reduced me to something resembling an animal’s life.

II

If I’m the coast and you’re the moon

raise my tide for me to comfort you

If I catapult onto the moon

spread your light as I come for you

Chorus

Awooooooo

Awooooooo

Awooooooo

Awooooooo

The worst part of solitary confinement was its open-endedness. I had no idea how long I would stay there: weeks, months, years? The rest of my life? Each time I heard the familiar clicking sound on the iron door that closed over my cell’s second, wooden door, I fantasized that someone had come to announce my release. They never had.

Compounding the physical and psychological punishment my jailers inflicted upon me was with the guilt I felt at having come to China instead of spending the summer in Boston with my family. I almost collapsed under the weight of all of the worst-case scenarios that ran through my mind. For example, my family has abandoned me, my friends have forgotten me, I will never see my children again, my parents are heartbroken, I will never work again. Hour after hour I was wracked by these thoughts of guilt and anxiety.

To cope, I resorted to daily prayers. Sometimes my prayers came hourly. This gave me the strength to face the next day, or the next hour. Then I decided to test my memory and exercise my mind by trying to remember complicated English words I had learned while studying in the United States. I was frightened when they would not return. To sharpen my mind, I began to write poems in my head.

Each night, as I lay on the stiff wooden board that served as my bed, I would spend hours staring out through the small window atop my cell searching for light and composing poems in my mind. When I had finished a poem, I would keep searching for better words, switching stanzas, and then running over the revised poem again. I repeated this process over and over. I ended up writing more than 100 poems of different lengths in this way, memorizing each word.

The first anniversary of 9/11 happened during my solitary confinement, and I wrote a poem commemorating that awful event.

“A Lamentation”

Two huge new waves of glory crashed down,

Cast so cruelly into history, the towering twins.

Five-thousand ships, with sails full-blown,

Now scattered and thrown.

To the Four Winds.

Civilization wept and groaned.

Greatness fell down on her knees to pray.

The red setting Sun, all arrayed in light,

On the back of a Swan,

Turns into Dark Night.

A crystal tear falls, seed upon a pillow.

The Moon grows, rising up from the sea,

Cradles her face within both her hands

Looking down at the world,

From her abode of peace.

An Old Man smiles, face riddled with ripples,

Undulating, propagating, ripples on ripples…

Another year’s tears, dreams, and emotions

Sink into the deep,

The deep, vast ocean.

Above the foam,

A white feather flies low,

Drifts to and fro,

Then floats…

A sail,

…without

……a boat.

Thanks to pressure from lawyers and elected officials in the United States, I was released from prison in April 2007 and returned to Boston later that summer.

In spite of the distinction I have reflexively (perhaps defensively) drawn between the two experiences, I now realize my story can provide some insight into how we, as newly isolated individuals, might respond to our new reality under quarantine.

First, we cannot deny that we are afraid. Admit it and confront it. Invite the fear in and examine it. Accept that, for the time-being, this is what life is right now. Don’t set yourself up for disappointment by expecting it all to end soon and suddenly. This is the life you are supposed to live right now.

Embrace that fact and you will probably find you are more equipped, stronger, and more gifted than you ever thought you were. Before I was placed in solitary confinement, I never imagined that I would be capable of writing a single poem, never mind a hundred poems. Though this is a very difficult time, it is also a very special time. If you are among the lucky who are able to shelter in place and work from home, it can be a sort of gift. You can teach yourself, deepen yourself, and find new value and meaning in your life. If you are home with children, you will cherish the memories of the extra time you now have to connect with them—even if some moments are undeniably difficult.

For me, it has allowed me to repair and strengthen my bond with Aaron. Being absent from his life for five-and-a-half years at such a young age had an enormous impact on him. He has been through a lot, and I have not forgiven myself for that. But he has emerged as an excellent singer and songwriter, leading a band called the Q-Tip Bandits. Although we are not quarantined in the same house, our connection is closer. We connect more often, check on each other’s safety, talk a lot about his songs, and discuss my drawings.

Yes, my drawings.

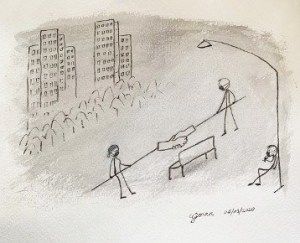

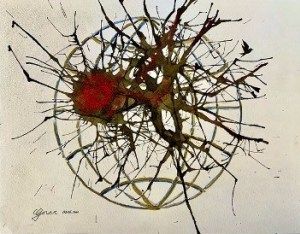

I have begun to draw while sheltering at home—something I had never done before. It was a potential ability but one in which I previously had no confidence. The initial inspiration for my minimalist line drawings was adapting to the “new normal.” A “life is elsewhere” escape from the disaster. But the theme of Aaron’s song “The Wolf” soon began to inspire many of my drawings. And now I am making drawings inspired by some of his other songs.

Aaron’s new album contains three songs in total and runs 12 minutes. I listen to it all the way through three times a day while doing exercises on the balcony of my apartment. Each time someone listens to his album, Aaron’s band gets paid one cent. On one of our calls, I told him that I was sending him three cents every day. “Cool,” he said. “That is very kind of you, Dad.” But I really don’t think it’s the money that he appreciates.

When we are all delivered from this evil, I plan to frame my drawings inspired by Aaron’s music. There will be many. And when we finally meet again, I will give them to him. After so many social distancing measures, I expect that hugging will continue to be discouraged between people who do not share the same house. But I don’t know how I’ll be able to stop myself when I see Aaron.

Paintings: Life Is Elsewhere

Minimal Line Drawings: